President Trump reached a deal with Canada and Mexico to restructure the North American Free Trade Agreement, hoping a new trilateral accord will reinvigorate the U.S. manufacturing sector.

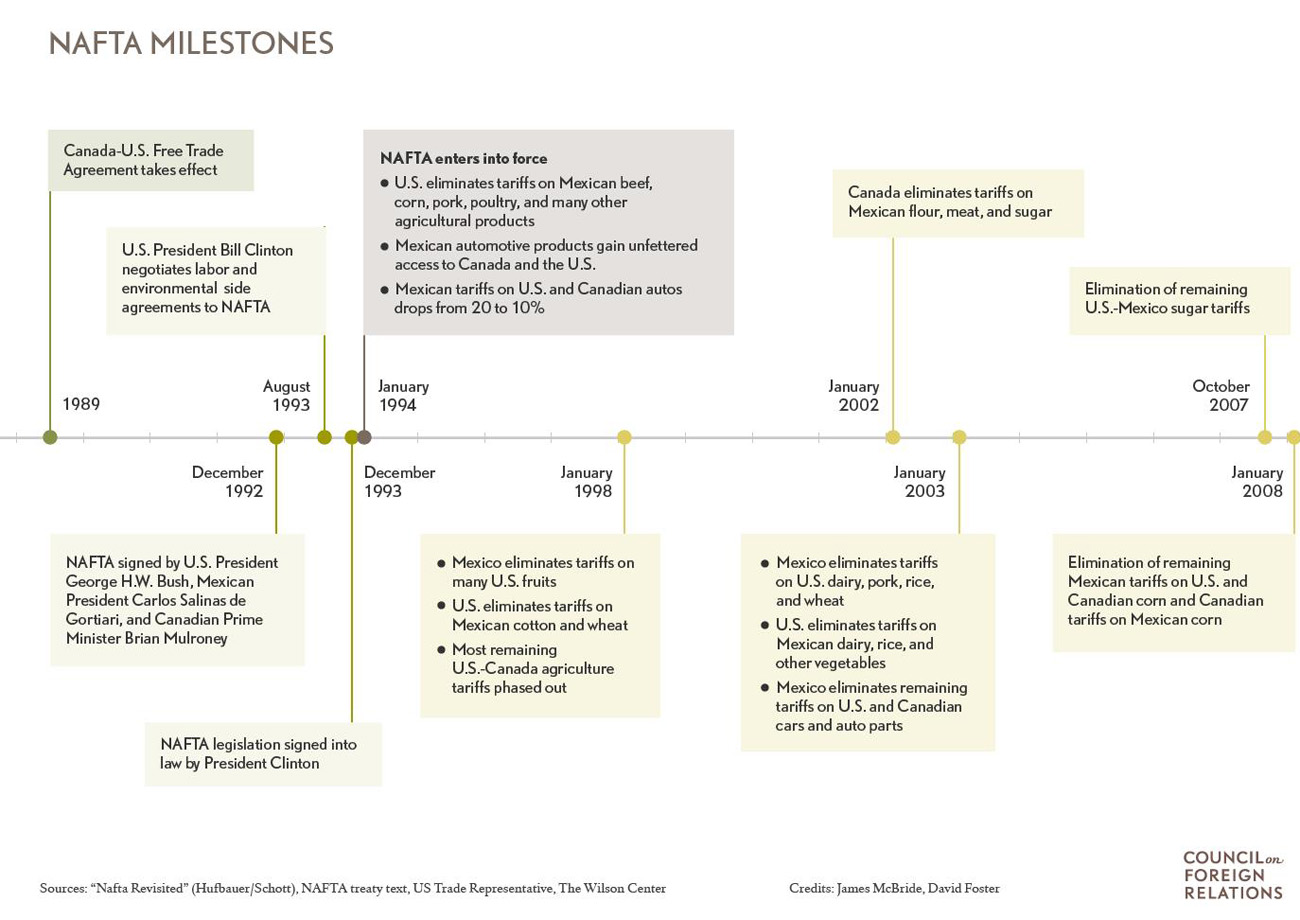

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was a three-country accord negotiated by the governments of Canada, Mexico, and the United States that entered into force in January 1994. NAFTA eliminated most tariffs on products traded between the three countries, with a major focus on liberalizing trade in agriculture, textiles, and automobile manufacturing. The deal also sought to protect intellectual property, establish dispute resolution mechanisms, and, through side agreements, implement labor and environmental safeguards.

More From Our ExpertsNAFTA fundamentally reshaped North American economic relations, driving unprecedented integration between the developed economies of Canada and the United States and Mexico’s developing one. In the United States, NAFTA originally enjoyed bipartisan backing; it was negotiated by Republican President George H.W. Bush, passed by a Democratic-controlled Congress, and was implemented under Democratic President Bill Clinton. Regional trade tripled under the agreement, and cross-border investment among the three countries also grew significantly.

Yet NAFTA was a perennial target in the broader debate over free trade. President Donald J. Trump says it undermined U.S. jobs and manufacturing, and in December 2019, his administration completed an updated version of the pact with Canada and Mexico, now known as the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). The USMCA won broad bipartisan support on Capitol Hill and entered into force on July 1, 2020.

When negotiations for NAFTA began in 1991, the goal for all three countries was the integration of Mexico with the developed, high-wage economies of the United States and Canada. The hope was that freer trade would bring stronger and steadier economic growth to Mexico, by providing new jobs and opportunities for its growing workforce and discouraging illegal migration. For the United States and Canada, Mexico was seen both as a promising market for exports and as a lower-cost investment location that could enhance the competitiveness of U.S. and Canadian companies.

The United States had already completed a free trade agreement (FTA) with Canada in 1988, but the addition of a less-developed country such as Mexico was unprecedented. Opponents of NAFTA seized on the wage differentials with Mexico, which had a per capita income just 30 percent [PDF] that of the United States. U.S. presidential candidate Ross Perot argued in 1992 that trade liberalization would lead to a “giant sucking sound” of U.S. jobs fleeing across the border. Supporters such as Presidents Bush and Clinton countered that the agreement would create hundreds of thousands of new jobs a year, while Mexican President Carlos Salinas de Gortari saw it as an opportunity to modernize the Mexican economy so that it would “export goods, not people.”

More From Our Experts

Eschewing these policy proposals, Trump instead made good on his campaign promise to renegotiate NAFTA. He used tariffs as bargaining leverage throughout the process, applying import tariffs on steel and aluminum in early 2018 and threatening to do the same with automobiles. Trump’s demands included more access to Canada’s highly protected dairy market, better labor protections, dispute resolution reform, and new rules for digital commerce.

In late 2019, the Trump administration won support from congressional Democrats for the USMCA after agreeing to incorporate stronger labor enforcement. In the updated pact, the parties settled on a number of changes: Rules of origin for the auto industry were tightened, requiring 75 percent of each vehicle to originate in the member countries, up from 62.5 percent; and new labor stipulations were added, requiring 40 percent of each vehicle to come from factories paying at least $16 per hour. A proposed expansion of intellectual property protections for U.S. pharmaceuticals—long a red line for U.S. trade negotiators—was sacrificed. The USMCA also significantly scales back the controversial investor-state dispute settlement mechanism, eliminating it entirely with Canada and limiting it to certain sectors with Mexico, including oil and gas and telecommunications.

As part of the deal, Canada agreed to allow more access to its dairy market and won several concessions in return. The USMCA will keep the Chapter 19 dispute panel, which Canada relies on to shield it from U.S. trade remedies. It also avoided a proposed five-year sunset clause, instead using a sixteen-year time frame with a review after six years.

In early 2020, the U.S. Congress approved the USMCA with large bipartisan majorities in both chambers, and the deal entered into force on July 1. Yet some critics have complained that the new rules of origin and minimum wage requirements are onerous and amount to government-managed trade. CFR’s Alden was more sanguine, saying the administration can take credit for restoring bipartisanship to U.S. trade policy. He warns, however, that “if this new hybrid of Trumpian nationalism and Democratic progressivism is what it now takes to do trade deals with the United States, there may be very few takers.”