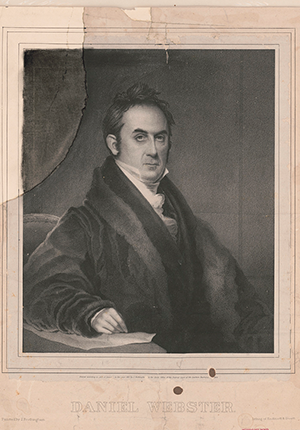

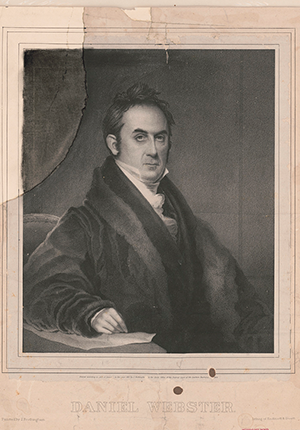

The “compact theory” of the Constitution first announced in the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions ultimately became the basis of far more radical theories of state rights. In 1832, for example, the state of South Carolina relied on the constitutional compact theories of John C. Calhoun in its Ordinance of Nullification which declared the federal Tariff of 1828 to be “null and void.” South Carolina insisted that each state, as an independently sovereign member of the original compact, had the authority to “nullify” federal laws the state believed to be unconstitutional. In one of the most famous congressional speeches in American history, Massachusetts Senator Daniel Webster rejected Calhoun’s compact theory and denied that states retained the sovereign right to nullify federal law. The Constitution, Webster declared, was not a compact among the states but an agreement between the sovereign people of the United States, a national people who pre-existed the creation of state governments. Whether a federal law violated the people’s Constitution was a matter left to the federal courts and not to the individual states. Webster’s nationalist understanding of the federal Constitution deeply influenced the constitutional theories of Abraham Lincoln and the Republican members of the Reconstruction Congress.

Class of 1921 Bicentennial Professor in the History of American Law and Liberty, and Professor of History at Princeton University

E. Claiborne Robins Distinguished Professor of Law at the University of Richmond

In 1789, and before this Constitution was adopted, the United States had already been in a union, more or less close, for fifteen years. At least as far back as the meeting of the first Congress, in 1774, they had been in some measure, and for some national purposes, united together. Before the Confederation of 1781, they had declared independence jointly, and had carried on the war jointly, both by sea and land; and this not as separate States, but as one people. . . .

[I]n the Constitution, it is the people who speak and not the States. The people ordain the Constitution, and therein address themselves to the States, and to the legislatures of the States, in the language of injunction and prohibition. The Constitution utters its behests in the name and by the authority of the people, and it does not exact from States any plighted public faith to maintain it. On the contrary, it makes its own preservation depend on individual duty and individual obligation. . . . [N]o State authority can dissolve the relations subsisting between the government of the United States and individuals; that nothing can dissolve these relations but revolution; and that, therefore, there can be no such thing as secession without revolution. . . .

The gentleman contends that each State may judge for itself of any alleged violation of the Constitution, and may finally decide for itself, and may execute its own decisions by its own power. All the recent proceedings in South Carolina are founded on this claim of right. Her convention has pronounced the revenue laws of the United States unconstitutional; and this decision she does not allow any authority of the United States to overrule or reverse. Of course she rejects the authority of Congress, because the very object of the ordinance is to reverse the decision of Congress; and she rejects, too, the authority of the courts of the United States, because she expressly prohibits all appeal to those courts. It is in order to sustain this asserted right of being her own judge, that she pronounces the Constitution of the United States to be but a compact, to which she is a party, and a sovereign party. If this be established, then the inference is supposed to follow, that, being sovereign, there is no power to control her decision; and her own judgment on her own compact is, and must be, conclusive. . . .

Mr. President, if the friends of nullification should be able to propagate their opinions, and give them practical effect, they would, in my judgment, prove themselves the most skillful “architects of ruin,” the most effectual extinguishers of high-raised expectation, the greatest blasters of human hopes, that any age has produced. They would stand up to proclaim, in tones which would pierce the ears of half the human race, that the last great experiment of representative government had failed. They would send forth sounds, at the hearing of which the doctrine of the divine right of kings would feel, even in its grave, a returning sensation of vitality and resuscitation. Millions of eyes, of those who now feed their inherent love of liberty on the success of the American example, would turn away from beholding our dismemberment, and find no place on earth whereon to rest their gratified sight. Amidst the incantations and orgies of nullification, secession, disunion, and revolution, would be celebrated the funeral rites of constitutional and republican liberty.